World War I interrupted his studies, and Szent-Györgyi served as a medic on the Italian and Russian fronts, receiving a Silver Medal for Valor before being wounded and discharged. He later admitted that his injury was self-inflicted -- he had carefully chosen a point on his left upper arm where a bullet would do no lasting damage, and shot himself to escape a war he saw as only a huge waste of life.

Discharged from the military, he attended medical school, and worked briefly in a Hungarian bacteriological laboratory, but quit after questioning experiments performed on Italian prisoners of war.

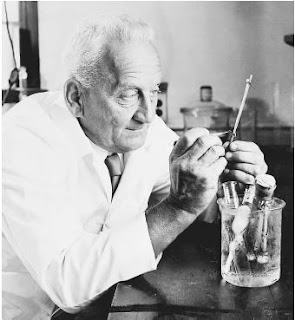

He wrote an article on the potato's respiratory mechanism which impressed Sir Frederick Hopkins, who invited Szent-Györgyi to join him at Cambridge. While working there, he discovered Vitamin C (ascorbic acid), first isolating almost an ounce of it in citrus fruit, certain vegetables, and adrenal glands. For his finding he was awarded the Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine in 1937. His further research showed that "hexuronic acid", as it was called, would prevent and counteract scurvy, and Szent-Györgyi later isolated vitamin B2, or riboflavin.

During World War II, he was deeply involved in Hungary's anti-fascist resistance, working to help Jews escape the country. He became a fugitive from Nazi authorities after Adolf Hitler ordered his arrest, but he was smuggled to safety in Sweden. After the war he returned to Hungary to oversee the rebuilding of Budapest's scientific institutions.

When he realized that Hungary's new communist regime would not allow unfettered research, Szent-Györgyi emigrated to America in 1947, where he researched metabolic processes of muscle cells, and the application of quantum physics to biochemical studies of cancer. He became an American citizen in 1955, and founded both the Institute for Muscle Research and the National Foundation for Cancer Research. In the 1960s he was an outspoken opponent of nuclear proliferation and America's war in Vietnam.